In June 1915, when Countess Lina Bianconcini Cavazza began to outline a new charitable institution in favor of soldiers fighting in the First World War, she almost immediately called her “precious” collaborator, Brigida (a.k.a. Gida) Rossi, appointed Chief Inspector of the Office for News to families of soldiers and sailors.

The relationship between Countess Cavazza and Gida Rossi dated to the time of the disastrous earthquake that struck Messina in December 1908, when Bologna contributed to the setup and operation of a laboratory with an attached laundry for women in order to promote the growth and emancipation of women in a manner that went beyond public charity. To complete the work and add “moral good” to the economic initiative, Gida also organized a holiday recreational center modeled on the one in Bologna, which she had directed in 1903, and where she gave lessons in mending and also managed the dance.

“To have life return from death,” and “It is the start of a new life,” Gida wrote in her diary, with a heavy load of responsibility. Three people came from Bologna to teach sewing and embroidery, along with the machines and the money needed to finance the business; a fourth person arrived to teach knitting. As she said, “My kingdom down there was the laundry,” which she had to start and make ready to handle a backlog of twenty thousand military blankets, piled up for months and requiring treatment. “Everything had to be turned on”: tubs and steam washer, storage room and water pipes, cart with lye, soap, brushes, baskets, lines to hang the wash, irons.

The work was organized in three departments: “washing, mending, ironing,” with the female workers, two ironers, the stoker, and others doing all sorts of mending and adjustments. On 8 August 1909, the laundry was inaugurated, and for Gida Rossi the plume of smoke from the boilers, the first large expanse of wash hanging out to dry in the sun “is perhaps worth more than my teaching diploma.” She wrote the Countess, “that from afar” she had continued to offer advice, and had a positive view of the company’s overall operation. “If you saw us now, you would say ‘good.’ The laundry works,” and concludes by saying that it would soon be able to cover operating expenses. Gida Rossi left the village on 5 September; back in Bologna, she continued her work on behalf of women and children with a project to open the Casa del Sole in Villa Armandi Avogli, called Villa delle Rose, in the Meloncello district, where in 1922 the children of disabled veterans, and especially veterans with tuberculosis, were treated and cared for: “the children of war,” aided by the Bologna Women’s Committee for disabled veterans, of which for a time she was the Chair.

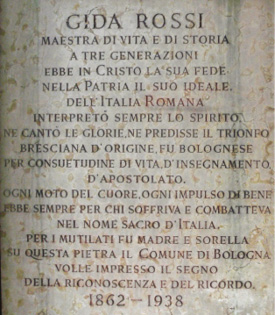

Gida Rossi died on 12 December 1938; she is remembered by a tombstone created by the artist Leonardo Bistolfi, with a bronze relief sculpture depicting Christ. A nursery school in the Borgo Panigale district is named after her.

References

Gida Rossi, Da ieri e oggi, (Le memorie d’una vecchia zitella) / Yesterday and today (The memoirs of an old spinster), Bologna, published by L. Cappelli, 1934.

Paola Furlan, Ufficio per notizie alle famiglie dei militari / Office for news to the families of soldiers, in “Vedere Oltre”, April 2019.

Mirella D’Ascenzo, Gida Rossi, in Memoria scolastica.it.

Maria Giovanna Bertani, Gida Rossi, 1862-1938, in History and memory, website of the City of Bologna.

.jpg)

.png)