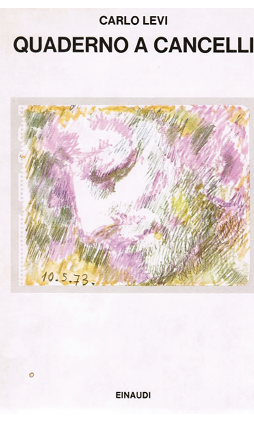

I believe there are moments in art that offer examples of strength that are able to overturn dramatic and even tragic situations and events. They occur by passing from a state of paralyzing pain to one of creative intensity that recovers one’s existence and potentials. These resurgences of energy take place by stimulating our mirror neurons and our heart. Carlo Levi (Turin, 29 November 1902 – Rome, 4 January 1975) was one of the great 20th-century masters, a clear and passionate thinker, writer, painter, and antifascist. Known especially for his novel “Christ stopped at Eboli,” he was an authoritative voice of the southern question in Italy after World War II. A trained doctor, he switched to art after his encounter with Felice Casorati and immediately achieved important results. In March 1934, Levi was accused of antifascist activities and arrested. On 15 March 1935, he was arrested again and imprisoned in Grassano, near Matera. He was later transferred to the town of Aliano, in the province of Matera, joined by his cousin Paola Levi, sister of the writer Natalia Ginzburg. His most famous novel, Christ stopped at Eboli, is based on this experience (he chose to be buried in Aliano). Linuccia Saba, his companion and daughter of the poet Umberto Saba, recalls that Carlo took a walk one night and had the impression that it was snowing. But it wasn’t: his eyes saw snow that wasn’t there, and he underwent an operation for a detached retina. He began drawing again almost immediately, seeing very little through a small binocular that he called his “little eye”. At first he sketched self-portraits with a pen or a pencil, using colored markers with explosions of purple, orange, yellow, and blue. One of his students built him two special frames (one for painting and one fit with metal wires forming squares to guide his hand), so he could insert a sheet behind the wires and use them to write or draw in the spaces. The title of his literary masterpiece Quaderno a cancelli (“fenced notebook,” published after his death), comes from a poem written by his close friend Rocco Scotellaro (1923 - 1953) dedicated to a girl in elementary school who uses a notebook with large squares to learn to write. In the book, Levi recalls the essential principles of his life, and his blindness elicits interior strength of emotional and introspective precision. Quaderno a cancelli is easy to find, but it’s almost impossible to find a catalog of Levi’s paintings from this period.

I was very fortunate to receive one as a gift on one of my stays in Matera. It was published in 2002 by Spes Milazzo, curated by Donato Sperduto, with an introduction by Giovanni Russo. 40 of the 145 drawings gleam with original expressiveness, technical variety, in blue or green ballpoint pen, lapis, colored pastels and felt. 21 drawings are undated; some of them were very probably done in February and March 1973. Levi painted a portrait of Pablo Neruda, who wrote the following: “While I sat for my portrait in his old studio, the Roman twilight slowly descended, the colors faded as if time, impatient, rapidly consumed them; I heard the horns of cars racing toward country roads, toward silence, toward the starry night. I was swallowed in darkness, but he continued to paint me. The silence devoured me, but he kept on, perhaps painting my skeleton. Because it was one or the other: either my bones were phosphorescent, or Carlo Levi was an owl, he had the scrutinizing eyes of the night bird.”

.jpg)

.png)